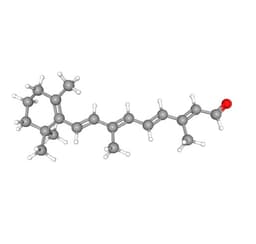

Retinaldehyde

Summary: A vitamin A aldehyde one step from retinoic acid, offering higher potency than retinol with lower irritation than tretinoin.

Published on: 11/08/2025

Retinaldehyde (retinal) is a vitamin A aldehyde that sits one step closer to the active form—retinoic acid—compared with retinol. It requires just one enzymatic conversion (retinal → retinoic acid), offering greater potential efficacy than retinol, which needs two steps [1].

Potency and Clinical Evidence

Several in vivo studies support retinal’s effectiveness at cosmetic-use concentrations. In a randomized, controlled trial, a 0.05% retinaldehyde cream produced wrinkle and skin roughness improvements comparable to 0.05% tretinoin, but with significantly fewer signs of irritation [3].

Additional data from broader reviews suggest that while tretinoin is the most potent and best-studied retinoid, retinaldehyde and retinol are considerably less irritating alternatives with potential clinical benefit [4]. Clinical evidence for retinaldehyde also includes smaller trials showing improvements in hydration, wrinkles, roughness, and other signs of photoaging with 0.05%–0.1% formulations [1].

Tolerability

Retinal is generally well tolerated, with a lower irritation profile than prescription tretinoin (retinoic acid) and comparable tolerability to retinol [1,3]. This favorable profile contributes to higher compliance rates in long-term use [3].

Stability & Formulation Approaches

Retinaldehyde is chemically unstable—prone to degradation by light, heat, and oxygen [2]. To mitigate this, advanced delivery systems such as pro-retinal nanoparticles [2] and cyclodextrin complexes [5] (among others) have been developed. These strategies help maintain stability, reduce irritation, and preserve efficacy in topical formulations.

References

-

Milosheska, D., et al. (2022). Use of retinoids in topical anti-aging treatments: A Focused Review of Clinical Evidence for Conventional and Nanoformulations Advances in Therapy.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12325-022-02319-7 -

Pisetpackdeekul, P. et al. (2016). Proretinal nanoparticles: stability, release, efficacy, and irritation. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 11, 3277–3286. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4959592/

-

Creidi, P. et al. (1998). Profilometric evaluation of photodamage after topical retinaldehyde and retinoic acid treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 39(6), 960–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70270-1

-

Mukherjee, S., Date, A., Weindl, G., et al. (2006). Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: An overview of clinical efficacy and safety. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 1(4), 327–348. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2699641/

-

Peter, D. et al. (2015). Retinaldehyde–cyclodextrin complex for topical skin therapy. Global Dermatology, 2(6): 232-236. https://doi.org/10.15761/GOD.1000161